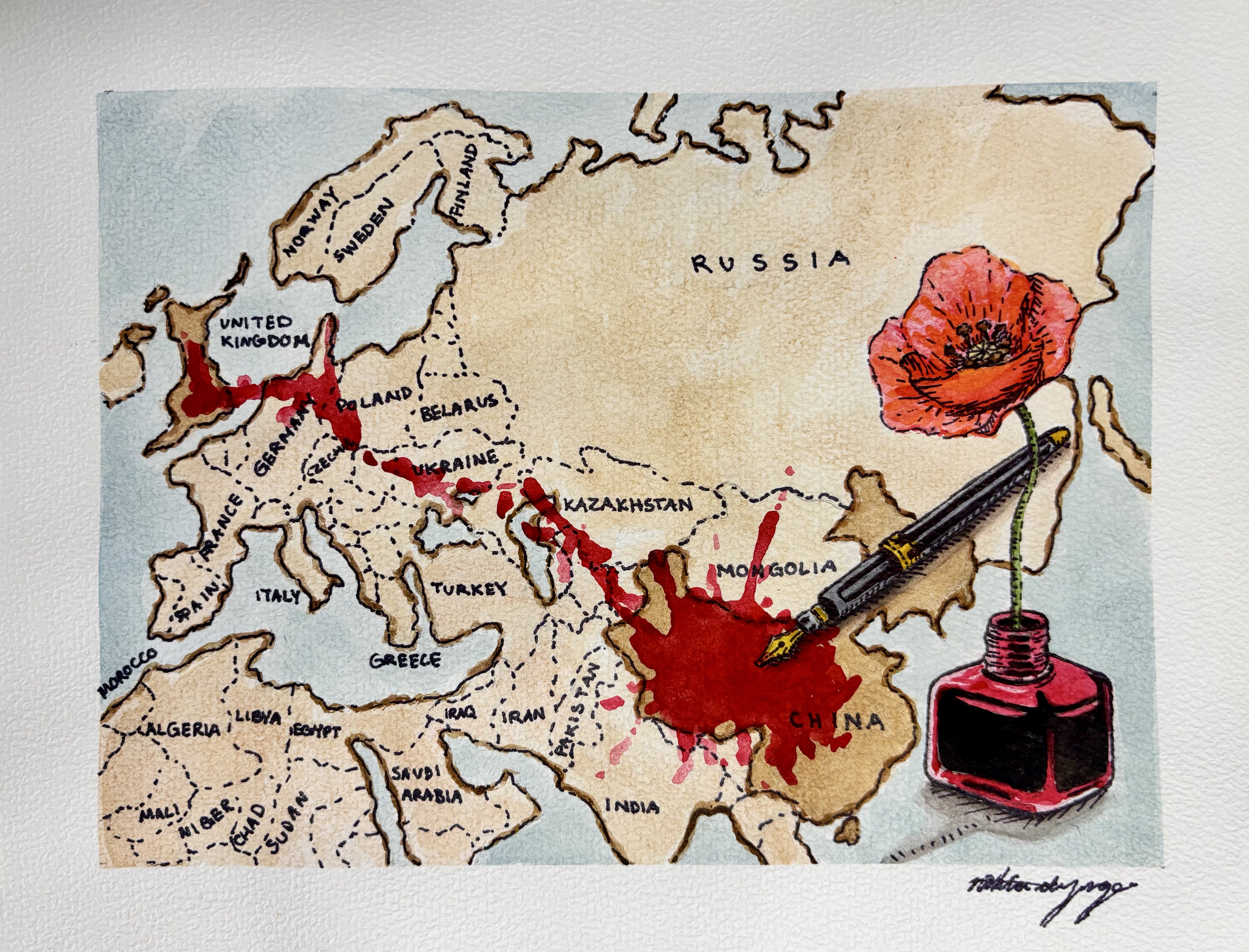

Cover Image: Painting by Nikita de Jonge, January 2026

Article by: Parmida Talebi, Contributing Writer

In the early nineteenth century, British ships sailed the South China Sea, hulls heavy with chests of opium grown in their Indian colonies. When the Qing Dynasty banned the drug in 1796, alarmed by its growing social and economic toll, Britain viewed the prohibition not as a deterrent, but an opportunity [1]. Illegal smuggling of opium began, addiction spread, and what began as trade evolved into the vicious weaponization of opium.

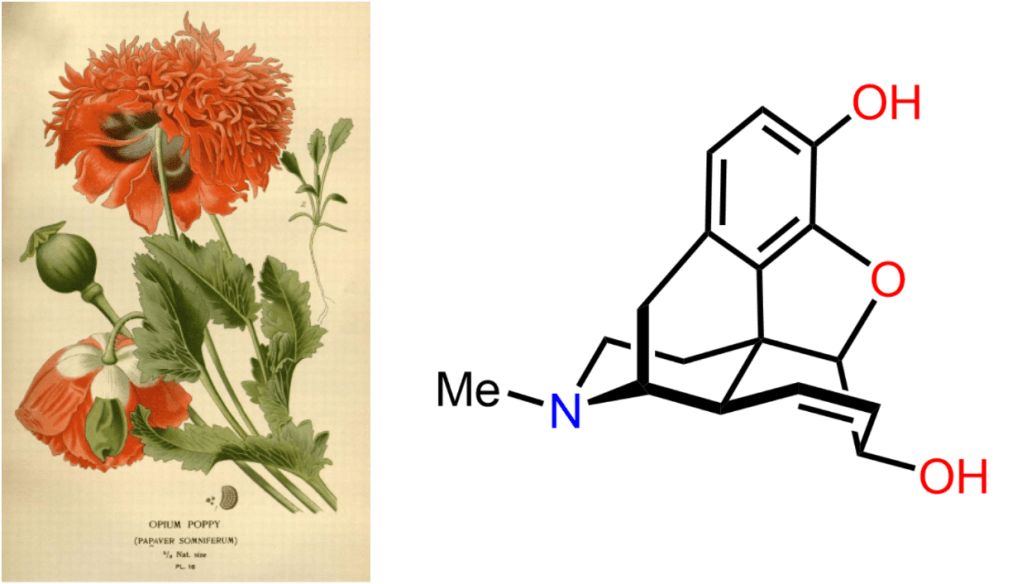

This knowledge, however, may seem trivial without understanding the biochemical power of opium. Its origins trace back to the Papaver somniferum, commonly known as the Poppy Plant [2]. Papaver, the genus, translates to “poppy” from Greek, while somniferum is “sleep-inducing;” an understatement of the potential risks that arise from its recreational use [3]. Approximately 20 organic, nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds called alkaloids make up the latex, or the “juice” harvested from a poppy [4]. The most abundant, and the key to opium’s power, is morphine. Named after the Greek god of dreams, Morpheus, morphine’s interactions with human opioid receptors in the nervous system equips it with unthinkable power [3]. Its defining mechanism is a carefully designed lock-and-key, with consequences deadly enough to cost a life. When unleashed on a nation, as history proves, morphine became the driving force that dragged an empire to its grave.

(Right) Three-dimensional chemical structure of morphine [6]

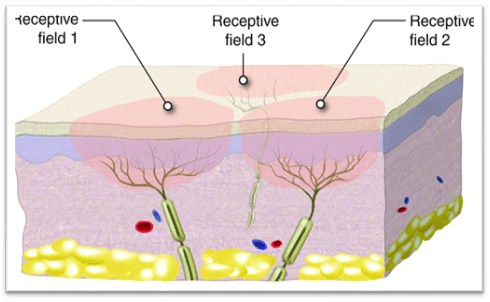

Built from five linked rings, several hydroxyl (OH) groups, and a nitrogen atom, morphine flawlessly complements the shape of the mu-opioid receptor (μ-OR or MOR) found in human nerve cell membranes [7]. This receptor only accepts molecules with the exact three-dimensional configuration and functional groups needed to activate it [4]. When morphine enters the bloodstream, μ-OR meets its perfect match. Morphine binds to the active site, providing the “key” to fit the “lock” [4]. Once bound, the receptor undergoes a conformational change that triggers a signal within the cell, slowing the transmission of pain signals from the peripheral to the central nervous system [7].

Morphine is an agonist, a broad class of compounds that bind to receptors in the body and elicit a physiological response [9]. As it isn’t made naturally, it is labelled a synthetic agonist, imitating the body’s own endorphins and often amplifying their effects [7]. This property, once discovered, earned morphine its place among the most powerful painkillers.

Unfortunately, while the mechanism of lock and fit seems perfectly designed, it comes with a tradeoff: the same receptor that soothes pain enslaves the body to a cycle of relief and withdrawal. When morphine, or another opioid, binds repeatedly to the mu-opioid receptor, it overstimulates the brain’s reward pathway, triggering surges of dopamine that produce euphoria [10]. Over time, taking opioids decreases the natural level of dopamine that the body produces, requiring more and more opioids to achieve the same sense of pain relief [11]. Even if one decides they wish to stop, it is excruciatingly difficult to control the cravings and stand the withdrawal symptoms, which include nausea, tremors, and diarrhea. While withdrawal is where physical dependence comes from, the cravings are psychological, and often associated with depression [11]. This is where addiction develops. As dependence takes control, the boundary between reality and a person’s own self-sabotaging subconscious begins to blur.

As a central-nervous system depressant, opium slows the body’s vital functions: heart rate, breathing, and neural activity [12]. It acts primarily by increasing the activity of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, which reduces the ability of neurons to send signals and communicate with one another [13]. This disruption produces an artificial soar of calmness and drowsiness that quickly turns into dangerous sedation. In the case of overdose, these effects can suppress respiration entirely, leading to unconsciousness or fatal respiratory failure [12].

Evidently, opium is catastrophic. Why, then, would any force want to magnify its danger and unleash it upon an entire civilization?

The answer lies in the deliberate economic strategies of the power-hungry British Empire, who viewed China’s trade surplus as a threat.

The roots of this imbalance trace back to 1715, when the English East India Company established its first formal trading post in Canton (modern-day Guangzhou) [14]. Both tobacco and opium were imported into China during this time, but use remained limited and regulated [14]. Meanwhile, British demand for Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain soared [15]. Seeing how China only accepted silver in exchange, Britain experienced an outflow of bullion [16]. This was unsustainable within Britain’s mercantilist economic system, which equated national power to precious metal reserves.

To alleviate this threat, British merchants turned to opium as an export weapon [17]. They began smuggling abundant amounts of the narcotic into China, cultivating a widespread dependency that alarmed the Qing government [18]. Although Chinese doctors had explored opium as a remedy for diarrhea and several other diseases during the Song Dynasty, civilians had not dared to smoke it recreationally [19]. As the smoking of opium exponentially rose, the court issued increasingly strict edicts, culminating in the 1799 prohibition on all opium importation [14]. Punishments were severe, to say the least. Users and traffickers were both liable to death [18]. Unfortunately, these restrictions had little effect on the population, and silver resources started to deplete. By 1838, the scale of the trade was staggering: over 40,000 chests of opium had been exported to China compared to 4,500 in 1810 [20]. More devastatingly, there were an estimated 13.5 million people addicted in 1906 [17].

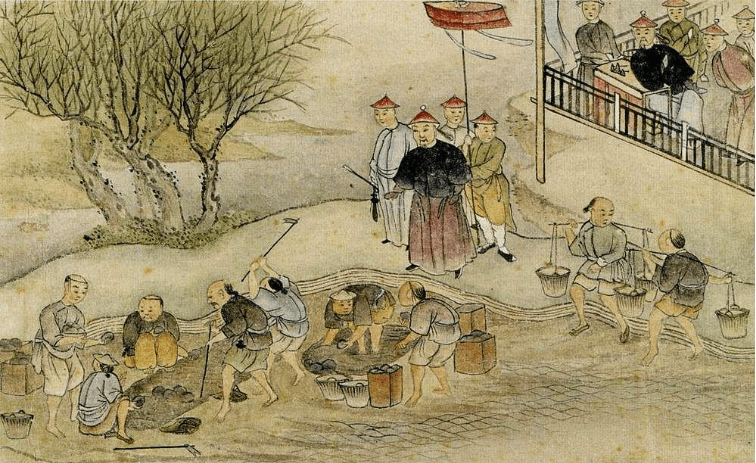

At the height of British smuggling, open conflict was provoked. In 1839, the emperor sent a special imperial commissioner, Lin Ze-xu, to handle the smuggling in Canton [18]. He demanded that the British merchants turn in all opium to him and confiscated 20,000 chests of opium [21]. Further, he wrote to Queen Victoria to invoke her sympathy for their cause and made a public display of opium destruction [22]. In one of his letters, Lin Ze-xu rightfully pointed out that Britain herself prohibited the smoking of opium yet felt no shame in subjugating China to its consequences [22]. Nevertheless, his efforts were fruitless in the end and China met defeat in the First Opium War (1839-1842), forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing [18]. The treaty pushed the already weakened government to open additional ports for “open trade” and cede Hong Kong [20].

By the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, China legalized domestic poppy cultivation due to growing fear of the West’s influence [14]. The crop proved highly profitable, and within several decades, domestic opium trade surpassed imports [17]. This expansion fueled the rise of opium dens, where people from various social classes gathered to smoke the drug for both medicinal and recreational purposes [24]. Differences in quality emerged based on the class of the opium den; wealthier patrons smoked opium with elaborately carved pipes, while lower-class users consumed it in communal settings, sharing paraphernalia [25].

Outside these dens, the social and economic consequences for the Chinese empire were devastating. Productivity plummeted within the working class, soldiers became unfit for service, and officials neglected their duties [17]. The cost for Britain’s profit was the undoing of China, marking the “Century of Humiliation”—in health, stability, and sovereignty [21].

The shadow cast by the weaponization of opium did not fade with the fall of the Qing Dynasty. The Republic of China’s attempts to eliminate the drug were largely unsuccessful, and by 1949 addiction had risen to nearly 20 million [17]. A temporary period of success followed under the 1950 anti-opium campaign, but reforms in the 1980s re-opened China to global markets [17]. As illicit drug trade continues to rise to this day, there is not only renewed trafficking and demand, but also renewed vulnerability. Heroin and alcohol have become major sources of addiction China, demonstrating the lingering effects of war [17].

The fuel to the fire, however, is not limited to the black market; over-prescription is a dangerous issue in the medicine industry. Following the invention of hypodermic needles in 1844, injection became a much more accessible and widespread method of drug prescription [26]. In the United States, hospitals accelerated this trend by prioritizing patient-reported pain relief [27]. Physicians are also responsible for prescribing high levels of opioids at once in rural areas for the sake of convenience [27].

Ultimately, the Opium Wars illustrate not only a historical tragedy, but a pattern: when a powerful group exploits a drug for profit, entire populations bear the consequences. Opium’s biochemical power allowed it to erode China from within, slithering through the weakened cracks left by the Qing government. Currently, cross-border trafficking, particularly from the Golden Triangle region, is the leading source of new synthetic drugs that reach China [17]. Globally, the opioid epidemic has spread to North America and impacts the rest of the globe, affecting over 60 million people [28]. Understanding the historical context behind the Opium Wars proves a valuable lesson: the devastation caused by opium was not inevitable. Preventing similar crises today relies on a collective effort to educate, intervene, and support those affected by addiction. The same substance that once broke an empire now serves as a responsibility that we share in stopping the cycle from repeating.

References

- The National Archives. Hong Kong and the Opium Wars – The National Archives. The National Archives. Published December 12, 2023. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/hong-kong-and-the-opium-wars/

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Exposure characterization. Opium Consumption – NCBI Bookshelf. Published 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586388/

- U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Intelligence. Opium Poppy Cultivation and Heroin Processing in Southeast Asia.; 1992. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/141189NCJRS.pdf

- Morphine & heroin. https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/rzepa/mim/drugs/html/morphine_text.htm

- Papaver somniferum, the Opium Poppy Plant. https://picryl.com/media/favourite-flowers-of-garden-and-greenhouse-pl-18-7789035562-638915

- Morphine Chemical Structure in 3D.; 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Morphine_chemical_structure_in_3D.png

- Edinoff AN, Kaplan LA, Khan S, et al. Full Opioid Agonists and Tramadol: Pharmacological and clinical considerations. Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. 2021;11(4):e119156. doi:10.5812/aapm.119156

- Receptive Fields. https://www.nursinghero.com/study-guides/austincc-ap1/pain

- Health Research Board. Agonist/Antagonist. HRB National Drugs Library. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/glossary/info/agonist

- Listos J *, Łupina M, Talarek S, et al. The mechanisms involved in morphine Addiction: An overview. Vol 20.; 2019:4302. doi:10.3390/ijms20174302

- Powledge TM. Addiction and the brain. BioScience. 1999;49(7):513-519. doi:10.2307/1313471

- Hilliard J. Central Nervous System Depressants – Addiction Center. Addiction Center. Published October 15, 2025. https://www.addictioncenter.com/drugs/drug-classifications/central-nervous-system-depressants/

- Huizen J. What is central nervous system (CNS) depression? Published February 15, 2023. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/314790#what-is-it

- Feige C, Miron JA. The opium wars, opium legalization and opium consumption in China. Applied Economics Letters. 2008;15(12):911-913. doi:10.1080/13504850600972295

- Derks H. 6 Tea for Opium Vice Versa. History of the Opium Problem: The Assault on the East. 2012;105:49-86. doi:10.1163/9789004225893_007

- Derks H. 8 The Invention of an English Opium Problem. History of the Opium Problem: The Assault on the East. 2012;105:105-120. doi:10.1163/9789004225893_009

- Lu L, Wang X. Drug addiction in China. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1141(1):304-317. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.025

- Canton-Alvarez JA. A Gift from the Buddhist Monastery: The Role of Buddhist Medical Practices in the Assimilation of the Opium Poppy in Chinese Medicine during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). Medical History. 2019;63(4):475-493. doi:10.1017/mdh.2019.45

- Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. The Opium Wars in China. Asia Pacific Curriculum. Published November 16, 2017. https://asiapacificcurriculum.ca/learning-module/opium-wars-china

- History of the opium problem: the assault on the East, ca. 1600-1950. Choice Reviews Online. 2012;50(03):50-1605. doi:10.5860/choice.50-1605

- Nakayama DK. The opium wars of China in the nineteenth century and America in the Twenty-First. The American Surgeon. 2023;90(2):327-331. doi:10.1177/00031348231192048

- Lin Z. LIN ZEXU, LETTER TO QUEEN VICTORIA (1839). The Chinese Repository. 1940;VIII–VIII(no 10):497-503. http://media.bloomsbury.com/rep/files/Primary%20Source%2013.0%20-%20Lin.pdf

- Destruction of opium at Humen.; 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Destruction_of_opium_at_Humen

- Drug Enforcement Administration Museum. Opium Pillow. DEA Museum. https://museum.dea.gov/museum-collection/collection-spotlight/artifact/opium-pillow

- Lamb A. How opium, imperialism boosted Chinese art trade. Harvard Gazette. Published January 11, 2024. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2023/11/how-opium-imperialism-boosted-chinese-art-trade/

- Mindo. Through the eye of the needle: A remarkable medical life. Medical Independent. Published December 4, 2018. https://www.medicalindependent.ie/in-the-news/news-features/through-the-eye-of-the-needle-a-remarkable-medical-life/

- Judd D, King CR, Galke C. The Opioid Epidemic: A review of the contributing factors, negative consequences, and best practices. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41621. doi:10.7759/cureus.41621

- Romero RB, Sánchez-Lira JA, Pasaran SS, et al. Implementing a decentralized opioid overdose prevention strategy in Mexico, a pending public policy issue. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas. 2023;23:100535. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2023.100535