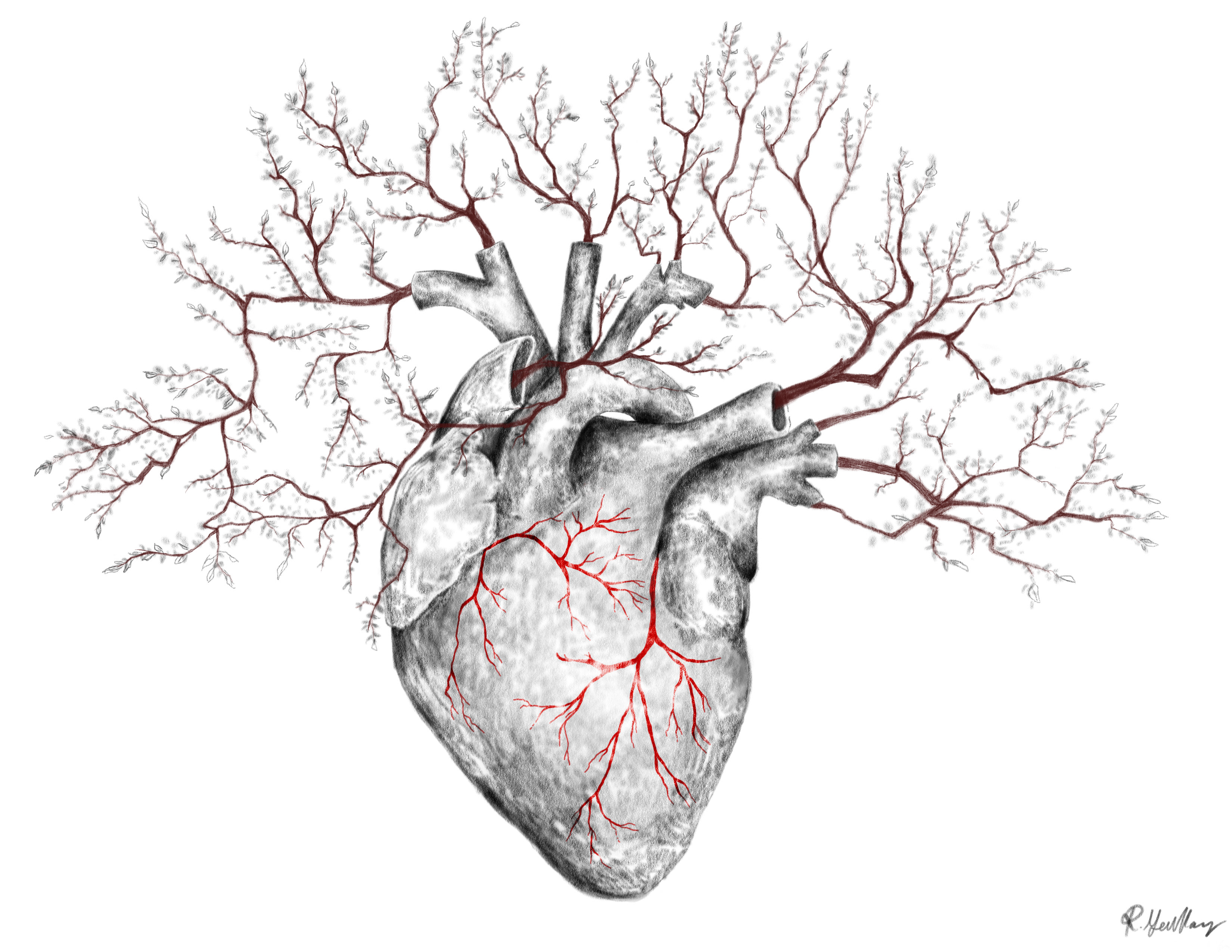

Cover Image: Drawing by Rachel Gerllays, February 2026

By: Flore Devernay, Contributing Writer

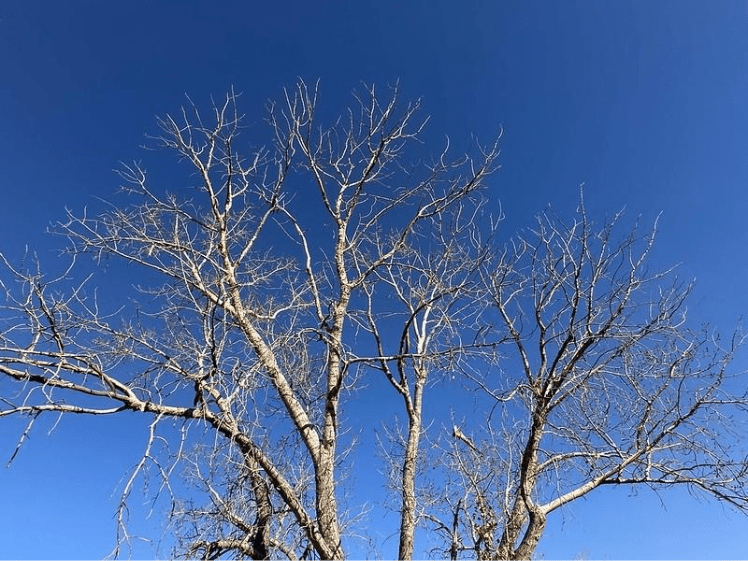

Before you read any further, go out to your nearest kitchen or dining hall, and pick out the freshest, greenest piece of broccoli there is. Now, take that broccoli outside and place it next to a tree. Notice anything? They look surprisingly similar…

If you’ve ever taken an anatomy class or even glanced at a heart drawing, you might notice that the branches of your tree somewhat look like blood vessels, or lungs. These unrelated objects all seem to hold the same structure, where zooming in or out would repeatedly produce the same pattern.

A self-similar, repeating pattern is the exact definition of fractals; a term coined by Benoit Mandelbrot, the “father of fractals”, in 1975 [1]. Because the pattern is never-ending as you zoom in or out, the perimeter is infinite within a finite area, an almost incomprehensible, yet fascinating property.

But how can a pattern have a finite area and infinite perimeter? To make sense of this property, mathematicians have defined fractals as “in between dimensions”. Let me explain.

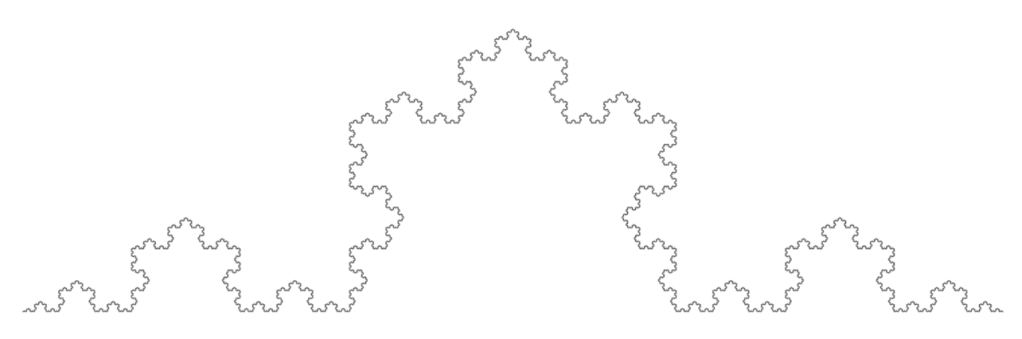

Simple shapes, like the ones you learned about in middle school geometry, can be associated with whole number dimensions. For example, a line is one dimension (length), a solid square is 2 dimensions (length and width), and a cube is 3 dimensions (length, width and depth). However, fractals don’t scale or fill space like these shapes do. Rather than being defined by the simple dimensions of length, width, and depth, mathematicians define each fractal as a unique non-integer Hausdorff dimension. A Hausorff dimension can be understood as the exact number of dimensions assigned to a shape for it to have a finite, non-zero size [2]. For example, the Koch curve (shown below) is more complicated than a line in one dimension, as it is an infinite pattern and thus an infinite length, but it also doesn’t fill the space like a solid square does in the second dimension. If we assigned it to the dimension 1, it would be infinite, but to the dimension 2 its size is 0, as it doesn’t have area. Its Hausdorff dimension is 1.26 [3].

Before we dive into another way to explain this strange dimension feature, let’s take a step back and introduce some simple concepts, to explain how fractals do not seem to scale within conventions for 1d, 2d, and 3d shapes.

Imagine taking a line and doubling it: you would get a line twice as long (21=2), doubling the length. For a solid 2D square, you would get a square four times as large, doubling the width and length (22=4). For a cube, your resulting cube would be eight times as large, doubling the width, length, and depth (23=8). Thus, doubling a simple shape like a line, square, or cube always results in a change by 2 to the power of the shape dimension.

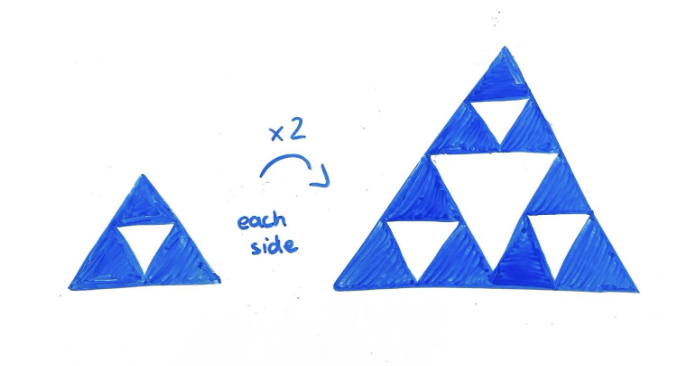

However, with the famous Sierpiński triangle fractal, doubling it would result in an area three times as big [4], as shown on the graphic below:

Thus, fractals represent shapes that are “in between dimensions,” whose infinitely detailed boundaries create an infinite perimeter, while the enclosed area remains finite.

Now, let’s get back to our broccoli, trees, rivers, lightning, you name it.

Why do all these objects and organisms resemble fractals?

Let’s think about trees, like the one you placed a broccoli next to earlier. They are largely defined as plants with a single stem and a branching canopy, but this branching pattern is far from random. First appearing 440 million years ago, this branching structure evolved as means to beat the increasing competition for space as land plants diversified. The fractal-like structure maximizes the capture of resources like sunlight above ground and water/nutrients below ground, efficiently filling the area with its infinite boundaries [5].

Now, what about the non-living, such as a lightning strike, cracks in the ceiling, or rivers? Lightning is a spark of electricity that jumps through the air when the cloud has become too charged for the air to hold it back. The electricity disperses in the easiest paths through the air. This creates a pattern of continuous branching that you know very well by now. All of these non-living fractals—such as cracks in the ceiling—are created because it is the easiest way to disperse energy coming from a single point, known as the constructal law [6].

It seems as if a multitude of objects and organisms are all using this fascinating mathematical shape to their own benefit. Fractals might just be the thread uniting it all: the living, the lifeless, the small, the vast, and you.

Website to explore fractals: https://fractaleverywhere.com/

References

- Mandelbrot, B. B. Fractals: Form, Chance, and Dimension (W. H. Freeman and Co., 1977).

- Dupor, T. Brownian Motion, Hausdorff Dimension, and Dimension Doubling. (2024).

- Lei, H. On the Hausdorff Dimension of the Visible Koch Curve. (2024).

- Chen, J. How to compute the dimension of a fractal. (2024). https://plus.maths.org/content/how-compute-dimension-fractal

- Chen, J. The power of patterns. (2025). https://thevarsity.ca/2025/03/09/the-power-of-patterns/

- Adrian Bejan, Sylvie Lorente,The constructal law and the evolution of design in nature,

- Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 8, Issue 3,2011, Pages 209-240, ISSN 1571-0645, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2011.05.010

Cover image: Illustrator for The Abstract (original work)