Cover Image and Figures: Auden Akinc, February 2026

By: Jacob Van Oorschot, Contributing Writer

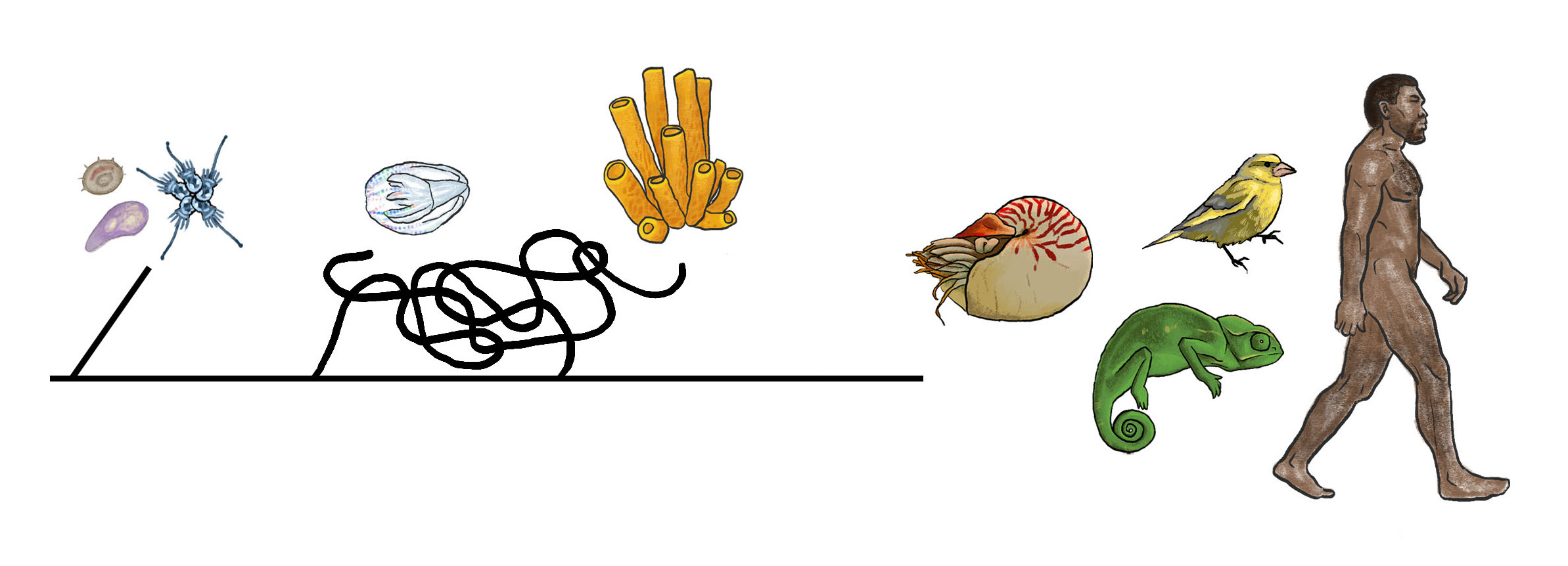

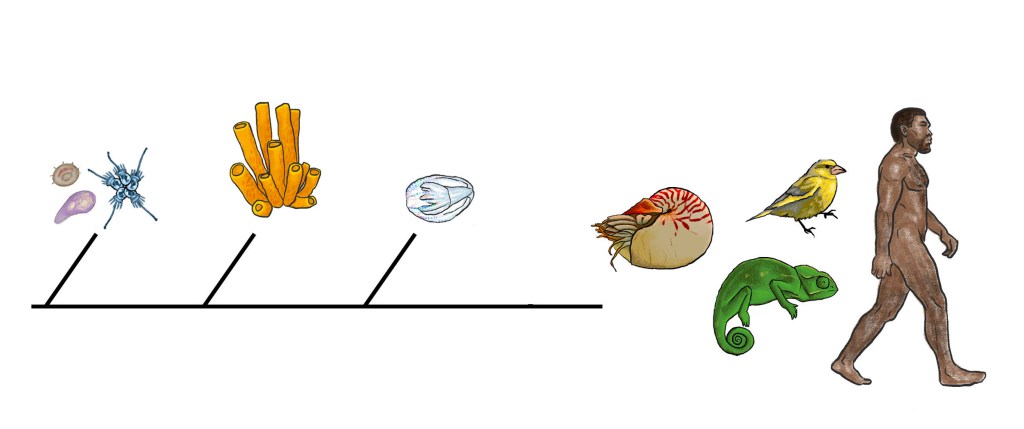

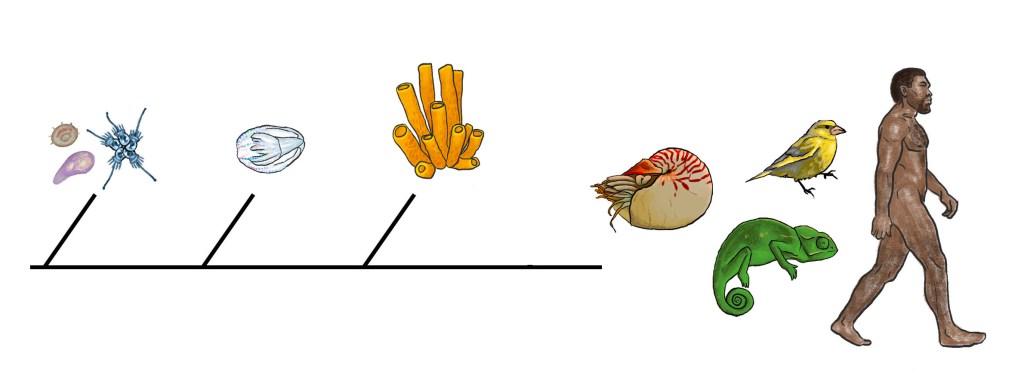

Who branched off first: comb jellies or sea sponges? Scientists have long debated whether comb jellies or sea sponges are more closely related to the other, more derived animals (including humans). The above diagram shows two possibilities: the sponges branching off first, making comb jellies more closely related to the “higher” animals, and the comb jellies branching off first. The former case has long been historically accepted, but recent studies involving genetic sequencing cast doubt on that model. Now, researchers have used a new approach investigating how genes are arranged relative to each other to lend further support to the latter case.

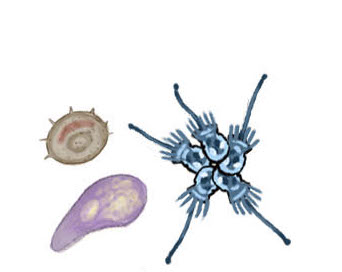

The sponges are a group of simple, shapeless organisms that seemingly resemble the single-celled organisms believed to be the evolutionary ancestors of animals. In contrast, ctenophores, colloquially known as “comb jellies,” have more structured body plans and nervous systems that outwardly resemble those found in the more complex animals. Based on these surface-level observations, biologists long believed that sponges branched off from the rest of animals first, followed by the comb jellies [1].

Modern genetics has allowed us to test the similarity of corresponding genes in different species of animals to investigate how closely those species are related. These methods, applied to the sponges-and-jellies debate, introduced uncertainty. Some studies made the surprising conclusion that comb jellies, and not sponges, branched off from the other animals first. But other analyses supported the converse, historically accepted hypothesis [2]. Could a novel, broader genetic approach clear these muddy waters?

Fishing—not for seafood, but for science—was about to play a role in resolving this debate and help definitively re-root this phylogenetic structure. Between two expeditions in 2015 and 2021, a team of scientists pulled sponges and comb jellies from the waters off the coast of California. But they weren’t on any ordinary fishing trips. Their catches were instead the subject of a genetic study published in 2023 that upended common beliefs about the fundamental structure of the tree of life [3]. The restructuring supported by their research has resounding implications for our understanding of how the evolutionary precursors of our nervous system (which allows humans to think, perceive, and have emotions) originated in the first place. It raises the possibility that complex neural systems originated multiple times independently over the course of early animal evolution.

So how did this genetic study differ from those that preceded it? The authors of the 2023 study zoom out to compare not any individual genes themselves, but rather how they are arranged relative to one another in DNA. Animals have their DNA divided into separate, physically distinct segments called chromosomes, between which genes usually do not move. In the rare cases where such rearrangements do occur, these changes are not readily reversible. Therefore, studying gene arrangements across chromosomes (through a process called “synteny analysis”) can reveal evolutionary changes preserved over exceedingly long time scales [3,4]. In the 2023 study, this approach was applied to sponges, comb jellies, and some related organisms. It provided evidence that, despite their primitive outward appearance, sponges are actually more closely related to the more derived animals than comb jellies are.

While this finding allows the sponges and ctenophores to be placed with more certainty into the fundamental structure of the tree of life, it raises further questions about the evolutionary origin of the nervous system in these early stages of animal evolution. Sponges lack the nerve cells found in comb jellies and the more derived animals [3]. Therefore, if sponges are indeed more closely related to the higher animals than comb jellies are, it leaves two unintuitive possibilities for how complex animal nervous systems originated. Either the ancestor of all living animals had the beginnings of a nervous system that was later lost in the sponges’ lineage, or the ctenophore nervous system arose independently of nervous systems in the more derived animals. This latter possibility would be a case of “convergent evolution” – the same process describing how flight arose independently in both bats and birds. New studies will be needed to begin to solve this ancient, underwater cold case.

The researchers may yet be out on further fishing expeditions, as making these syntenic comparisons using a greater number of comb jellies and sponges would strengthen their results. Synteny analysis also shows promise in resolving uncertainties around even older events in evolutionary history. Take another open question in biology: which groups branched off first in the evolution of eukaryotes (the domain of organisms consisting of animals, plants, fungi and their nearest single-celled relatives) [5]? Analyzing the organization of genes within chromosomes could be applied to eukaryotes as a whole to determine the position of the earliest divisions within their (really our) tree.

Looks can be deceiving. Just because an organism appears simpler than another doesn’t mean it is necessarily more primitive. And when looking at extant (“modern day”) animals, it’s important to remember that all the organisms we see around us have spent the same amount of time evolving. To call an animal further from ourselves on the tree of life more primitive is a somewhat subjective judgement anyways. For any division in the tree of life, it is easy to assume that the basal clade (the group of organisms that branched off earlier in history) is representative of the common ancestor that existed just before that divergence. But this need not be the case—the basal clade has had just as much opportunity (temporally, at least) to evolve since branching off.

In the case of the split between comb jellies or sponges and the more derived animals, the time since branching is measured in hundreds of millions of years [3]. Looking into events this old leads to a lot of uncertainty, no matter how precise one’s investigation is, so there is still room to dispute the conclusion that comb jellies branched off first from the more derived animals. But if we do assume this model to be true, then we are left to speculate on the evolutionary history of the nervous system and consider whether the nervous system was lost in sponges, or arose independently in comb jellies. I find either possibility difficult to wrap my head around. Which do you believe?

References

- Dawkins R, Wong Y . 2004. The ancestor’s tale: a pilgrimage to the dawn of evolution. 1st Edition. Boston (MA): Mariner Books.

- Li Y , Shen X-X, Evans B, Dunn CW, Rokas A. 2021. Rooting the Animal Tree of Life. Mol Biol and Evol. 38:4322–4333.

- Schultz DT, Haddock SHD, Bredeson JV, Green RE, Simakov O, Rokhsar DS. 2023. Ancient gene linkages support ctenophores as sister to other animals. Nature 618:110–117.

- Zhao T, Schranz ME. 2017. Network approaches for plant phylogenomic synteny analysis. Curr Opin in Plant Biol. 36:129–134.

- Burki F, Roger AJ, Brown MW, Simpson AGB. 2020. The new tree of eukaryotes. Trends Ecol & Evol. 35:43–55.