By The Abstract Editors: Kiarah Geertsema, Natalie Co, and Adele Lopes

In partnership with McGill’s Office of Science Education

We, the editors of The Abstract 2024-2025, had the immense pleasure of speaking with ten of Building 21’s presenters at McGill’s Undergraduate Science Showcase this year. These inspired undergraduates surprised us in not only sharing their projects, but also their collective hope for a more imaginative and collaborative future. This post features their projects, creativity, and vision. We hope this feature will motivate you to think outside of the confines of your field and realize that the gap between disciplines is traversable—if it even exists in the first place.

For a full list of the projects featured and their respective authors, please visit Appendix 1.

Table of Contents

- Building 21

- No Man is an Island

- A Testament to Collaborative Curiosity

- Bridging the Major Gap: Why do Disciplinary Silos Exist?

- The Gap Between Arts and Science

- Future Directions

- Building 21 Has Been an Important Space for Many

- Advice for Beginning Interdisciplinary Research

- Works Cited

- Appendix 1

Building 21

Building 21 (B21), McGill University’s “interdisciplinary idea lab”, has been providing financial and intellectual support to scholars pursuing innovative research since 2017. The organization helps creative individuals explore beyond the confines of conventional research and provides a space for co-mentorship and curiosity.

All of the showcase presenters we interviewed for this piece are currently “BLUE Scholars”. These are research students in B21’s BLUE (Beautiful, Limitless, Unconstrained Exploration) Programs who are undertaking “outside of the box” research. They are dedicated, inquisitive, and open-minded students with one thing in common: a passion for interdisciplinary, unconventional exploration.

Building 21 is unfortunately facing closure this month, on April 30th, 2025, due to McGill University’s budget cuts. If someone you know has benefited from the support of B21, or if this article inspires you, we encourage you to check out or share Building 21’s crowd-funding page.

No Man Is an Island

Many of the lingering questions about our world cannot be faced alone. Have you ever wondered, how could we better the world? Maybe you’ve thought to yourself, if we changed our view of the surrounding world, would we care more to save it? Or perhaps you’ve contemplated, how could we improve our perceptions of ourselves and each other? These are all examples of questions that really cannot be answered until we move past the disciplinary walls ingrained in large institutions such as universities.

As students, we do our best to answer questions every day, but the simple fact remains: a student working alone, even a multitude of experts from one field working alone, could not begin to scratch the surface of most of the lingering questions of our world and the universe beyond it. Collaboration is imperative to research—both intradisciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration alike.

Of course, our questions only multiply with this perspective. Now we have to question ourselves, too!

How is our generation working together to better the world? If our inherent view of the environment around us can be bettered, how are we doing so? What about our perceptions of ourselves and each other; how are we collaborating to improve those?

We are each other’s best resource. How are we grabbing hold of our educations and grabbing hold of each other to make positive change? The B21 scholars are examples of how this can be done; many of them are in fact wrestling with the above questions. These students are not constrained by the limits of traditional study and the limits of their own mind; as such, they can ask many sorts of questions and go to many sorts of people to ask them.

A project by B21 scholar Victoria Macheroub Kramer [Appendix 1A] provides a key takeaway to this discussion of collaboration. Macheroub Kramer’s study and related podcast, The Neurovation Project, seek to understand the relationships between neurodivergence, entrepreneurship, and innovation, and to ultimately challenge the negative perceptions surrounding neurodivergent individuals. Macheroub Kramer took on this project upon noticing that many very successful entrepreneurs are neurodivergent, but that, for some reason, we tend to focus on what neurodivergent people can’t do. Through The Neurovation Project, Macheroub Kramer interviews neurodivergent entrepreneurs and founders (as well as researchers, medical practitioners, professors, among others), to switch the focus from their weaknesses to their strengths. While discussing these interviews with neurodivergent individuals, Macheroub Kramer recounts the general feelings expressed:

“All of them have said that there were some hardships that they faced when they were younger, but that they were able to overcome them with a very good support system from their family, friends or other resources. All of them pursued entrepreneurship and innovation since it came to them very naturally and they’re very passionate about what they do. There seems to be a bit of an intrinsic motivation rather than a profit driven approach for them all.” (Macheroub Kramer)

Macheroub Kramer explains that neurodivergent individuals often have distinct and clear strengths: “The literature has shown that people who are dyslexic are naturally more creative, and some research shows that people who have ADHD symptoms are better suited for entrepreneurship.” We all need each other and we can learn from all sorts of people. No person is an island, and more than that, every person, no matter who, may offer insight and expertise where we least expect it.

Victoria Macheroub Kramer: Uncovering the Connections Between Neurodiversity, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation

A Testament to Collaborative Curiosity

One group of B21 presenters is specifically prioritizing collaborative curiosity in their approach. Isabella Zhou, Anastacia Raniuk, Roberto Concepcion, and their team [Appendix 1B] are brainstorming how we can grow the economy while healing nature. The beauty of their project is in the collaborative approach they are taking; they make room for fruitful discussion about a heavy and multifaceted subject. Their project is definitely “unconventional” in the way it prioritizes asking questions and hearing new points of view above achieving results. In fact, their results are really the questions they succeed in asking.

“Rather than jumping to the answers and the solutions, we wanted to go back to the beginning and see, are the right questions being asked, and what new questions can we ask? And specifically, how can diverse fields be a part of our project? So there’s sustainability, finance, cognitive science, computer science, sociology and so on. What kind of new questions can they ask? What kind of perspectives and avenues that haven’t been taken before can they take? And how can we see this question entirely differently?” (Raniuk)

“We’re not necessarily looking for solutions. It’s more that we’re trying to demonstrate a new frame of thinking to approach a problem.” (Concepcion)

Though quite different from modern research methodology, it must be remembered that asking questions is an integral part of the scientific method. As Zhou puts it: “I think progress in any direction has to start with discussions. It has to start with questions that people haven’t asked before.”

This project inherently challenges the go, go, go, fast-paced style of research. Raniuk challenges classical methodology in asking a simple question: “Science starts from questions and it starts from hypotheses, so why should we rush past that?” Make room for collaboration. Make room for questions. Slow down and take time to think things through. You might even make more progress that way.

The truth of the matter is, you can ask as many questions as you want, but if you’re only asking yourself, then you’re not making the most of your questions. Ask with curiosity or ask intelligently or ask ignorantly. Ask any way at all. But consider broadening your audience, even to those you think won’t have answers.

Anastacia Raniuk (left), Isabella Zhou (right): A Regenerative Economy: How Can We Achieve Growth while Healing Nature?

Bridging the Major Gap: Why do Disciplinary Silos Exist?

The Major gap (no pun intended)—the invisible but certainly palpable space between majors—is ubiquitous across universities. Students stay within their bubbles because the educational system is made that way. Many disciplines are regarded as very separate, and so we naturally separate ourselves by our fields of study.

One group of presenters we interviewed, Anu Khanna and Emily Zheng [Appendix 1C], have a podcast, appropriately named The Bridge, which addresses the lack of overlap between disciplines at McGill University. The Bridge is “breaking down inter-faculty stereotypes to repair communication channels across different faculties, within the McGill infrastructure” (Zheng). Khanna and Zheng, both third year Finance students at McGill, began their podcast upon recognizing the lack of connectedness between Desautels Faculty of Management and other faculties. They saw their program’s isolation and questioned it:

“Why is it that within McGill we are so siloed, if, in reality, when we go out into the real world, we actually have to interact with every single discipline? Professionals from all different backgrounds? Isn’t this a disservice to our students when we think about university as a preparation for the real world, if everyone sticks within their own faculty, and we don’t learn how to engage and collaborate with different disciplines?” (Zheng)

Khanna and Zheng’s podcast not only discusses the implications of the Major gap, but also dissects possible root causes and potential solutions. They understand how easy it is to relate to your faculty and form conceptions about others.

“Our hypothesis is that maybe there’s some stereotyping, initially, and some predisposed assumptions about different faculties that are preventing students from traveling across these barriers. There’s also obviously the building, the physical infrastructure of the university. And we’re also exploring other other things, like cultural identity that one could attribute to their own faculty that makes it comfortable for them to stay within their silos.” (Zheng)

Meeting with people from other faculties may even be considered a waste of time. For those students who are so enthralled in their career path, doing anything it takes to build up their reputation or add to their list of relevant professional experiences, it may be hard to look beyond the walls of their major. As Zheng puts it, “we have clubs that are designed for academic purposes to build resumes. We have clubs that connect people by passion. But due to time constraints, people don’t prioritize those ones as much as the ones that build your resume.”

Disciplinary silos are present from the get go. Think about the McGill Science Undergraduate Society’s Frosh week. Before classes even begin, students are acquainted with their program members only! “It’s day one when you come onto campus, you’re already separated,” Zheng notes.

This duo has interviewed McGill’s administration to address these problems:

“We did interview the McGill administrative team. There are administrative hurdles to this, because organizational structure is also very important to an institution of this size. If you were to disassemble faculties completely, I’m not sure we would run smoothly either. So it’s about finding a balance.”

It seems that there are many factors contributing to the size of the Major gap. It’s partly institutional, partly social, and partly personal.

Emily Zheng: The Bridge

The Gap Between Arts and Science

Perhaps the most evident barrier between disciplines is between Arts and Science. While the “scientific” presentations at McGill’s 2025 Undergraduate Science Showcase took place on the 3rd floor of the University Centre building, B21’s research students presented their work on the second floor under the title “Building 21 Creative Projects” and the label of being the more “artistic” projects. Three of the B21 scholars we interviewed had unique and insightful thoughts, particularly on the connections between Arts and Science.

Isabelle Guo: Building and Examining Biofutures with Speculative Fiction

Isabelle Guo [Appendix 1D], a Neuroscience student, is undertaking a multimedia, speculative fiction project called Genotopia that considers the direction of both science and social norms to imagine the future of humanity. Guo’s work wrestles with what it might mean to be human in a world with ever-changing ideas of what consciousness truly is. As a B21 scholar, Guo combines the study of Neuroscience with worldbuilding and creative writing, elegantly connecting Arts and Science:

“I think art can really highlight the beauty of science, and can highlight some of the implicit aspects that we find to be really beautiful on their own, like a starry night sky or the inside of a cell. And vice versa: science can inform a lot of beauties about art; even math can inform a lot of beauty about art.” (Guo)

Interestingly, Guo feels that many of the qualities that make good scientists also make good artists, pointing out that “to think critically about abstract systems, to be creative, or to slot things together in a way you haven’t seen before” are highly valued skills in both Arts and Science.

Laurence Liang: Improving Efficient Computing through Hardware and Software Co-Design

Laurence Liang [Appendix 1E], a U4 Mechanical Engineering major, is investigating the ever-growing world of AI through a lens of beneficial social applications–specifically, making large language models accessible to the general population. These models often require very large computers to run, putting them out of reach of the average person that relies mostly on their smartphone in their day-to-day life. Although the project is largely in the conceptual stage, Liang’s project aims to meaningfully compress language models into an application or website:

“…you’d be able to download a Language model that runs actually within your smartphone itself.”

The benefits of hosting a language model on a smartphone extend beyond convenience.

“…you’d have much more control over how your Language model is hosted. You’d definitely have some control over the privacy aspect of it. It would give you more ownership, having smaller Language models.” (Liang)

Mathematically speaking, this project tackles an interesting problem. But, like many other B21 projects, Laurence’s research extends beyond any singular field. Ultimately, the convenience and autonomy of such small language models speaks to the idea of usefulness–a concept that eludes categorization.

“One thing that was an essential part of my project was asking folks ‘how do you make a model useful?’ Because when you want to make something useful it’s hard to define what it is. I think that by a definition, that kind of extends to artistic and social processes.” (Liang)

At the end of the day, the end goal of any kind of research is inherently social. We hope to gain theoretical and practical knowledge for our own human benefit. Regardless of whether research appears to transcend disciplinary boundaries or whether it seems to dive deeply into a thorough examination of a particular area, the implications of knowledge can extend beyond the immediate bounds of its field. Even in a largely technology-focused project, the act of researching can bridge the ostensible barrier between Arts and Science.

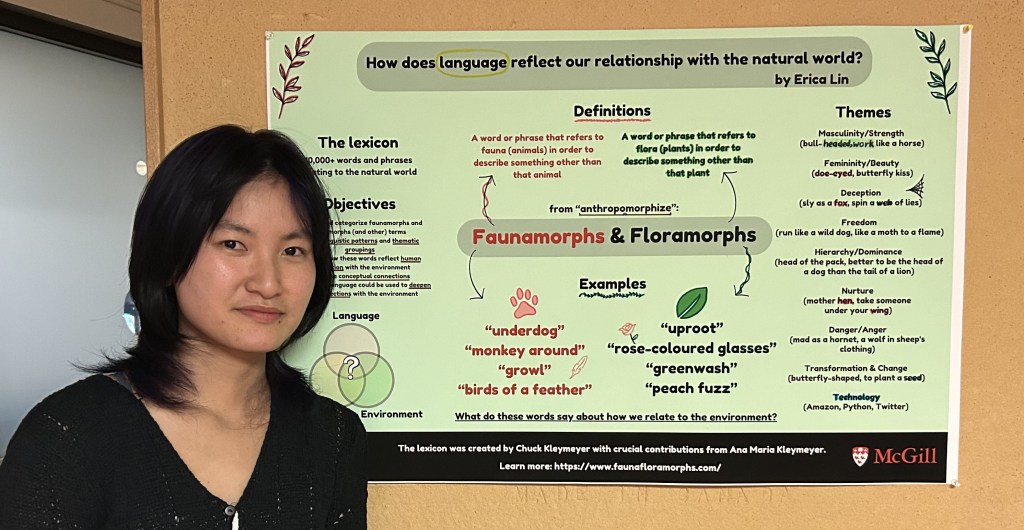

Erica Lin: Lexicon to Deepen the Relationship between Humans and the Environment

Erica Lin [Appendix 1F], studying Environmental Sustainability at McGill, has the unique perspective of being in a Bachelor of Arts and Science at McGill. B21 has allowed Lin to step outside of sustainability into the world of linguistics. Lin’s study uses AI, specifically ChatGPT and Obsidian, to identify, sort, and visualize words related to nature into semantic categories.

“My project is trying to analyze a data set of thousands of words that all come from the natural world. For example, underdogs, monkey around, birds of a feather. These are all phrases that we use that come from the animal world. Uproot, green wash, peach fuzz. These are words that we use that come from the plant world. I feel these words must say something about our underlying relationship with the environment. I’m trying to explore how these words might change in the future to reflect our changing attitudes towards the environment.” (Lin)

A unique blend of disciplines, Lin’s project explores social and linguistic intersections with the natural world surrounding us, as well as how our interactions with the natural world may be influenced by subconscious preconceptions.

Lin notes that we often undertake environmental study because we recognize the beauty of nature and want to fight for it: “I feel, especially with sustainability, there’s always a human component. I care about nature because I care about people and I care about their relationship with the planet.” Lin embraces Arts and Science as overlapping disciplines and encourages us to think simply about this topic, to realize that scientific study, which attempts to understand our world, is also inherently a social and artistic venture. Medicine is studied for people, sustainability for humans and other living things, physics for all types of social applications. Science itself is a statement to a general appreciation of the intricacies of life and living things.

To take things further, these remarks surely translate to disciplines in general. We subconsciously understand our human relatedness, so why do we not go beyond appreciation and embrace teamwork in our daily lives?

Katherine Reed: Preserving Privacy

Katherine Reed [Appendix 1G] is exploring the socially and physically realized concept of privacy. Reed’s project, “Preserving Privacy,” employs anthropology and psychology to understand why and how privacy is important to humans, and how privacy is and has been threatened. Interestingly, the project investigates material culture—the material aspect of culture that encompasses everything from handbags to locks and keys—to reveal the tangible significance of privacy. When asked how this project bridges the gap between Arts and Science, Reed gave a powerful response: “I think that the gap between science and art is not actually there. Because well, how you communicate science is an art.”

To scientists, Reed gives this advice:

“I think that there’s something intrinsically artistic about scientific inquiry. The creative aspect that leads you from one curiosity to the next is still present in how artists develop their work. But aside from that, because I believe the best change is always an action, just take yourself to an art gallery!” (Reed)

Language, literature, and material culture are aspects of this world that everyone interacts with daily, whether they realize or not. To the scientists: explore these elements. To the artists, your craft is intrinsically linked to properties scientists study; as science and technology progress, so do the possibilities for art!

Future Directions

The question remains: how can we tangibly introduce interdisciplinary research into the professional and academic spheres? Some of the B21 presenters have shared with us their hopes for progress and how we can begin to collaborate between fields and disciplines.

Emily Zheng, whose podcast discusses this topic, hopes that B21’s interdisciplinarity will serve as an example to McGill in its entirety, and by extension, universities everywhere: “Ideally, McGill becomes a space like Building 21 and hopefully this problem will also get realized in other universities.” Zheng, who has interviewed the McGill administration alongside fellow undergrad, Anu Khanna, feels it is important to continue discussing with McGill’s administration how the Major gap can be realistically bridged.

“We have to work with the McGill administrative team, which we are doing currently, to try and figure out what we could compromise.” (Zheng)

Khanna and Zheng are working to introduce collaborative events to McGill campus and possibly integrate academic incentive to motivate people to start bridging this gap:

“And I don’t know if it’s going to work, but it’s something I’ve been thinking about as a good starting point. Because you need a starting point, and then, just like bacteria will spread naturally, connections to save a network will grow by themselves. You need to first get connected with at least one person who has more connections with their faculties.” (Zheng)

Joshua Weinstein [Appendix 1H], a U4 Honours Software student, is also undertaking a project that engenders interdisciplinary collaboration. Weinstein hopes to build a network of various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that tackle a variety of issues, from homelessness and hunger to climate concerns. While these seemingly disparate organizations appear to tackle different issues, they are inherently intertwined in their ultimate mission of creating a better future.

“But because that’s so strongly implied, I think sometimes we forget to make it explicit and make it clear that we actually are working together, that we can see those things. And so what I’ve taken to is trying to create this new approach, where really at the core, the idea, rather than approaching one of these concrete problems, the idea is more to connect the different pieces of the world that are approaching these problems and try to make it so that people feel more like this is a joint effort…” (Weinstein)

What does this actually look like?

“So broadly speaking, it’s about the philosophy of trying to connect people across different boundaries we have, both in technology and in society. And coming up with initiative systems, a network that tries to connect across those boundaries…as a way of bridging those gaps and building an open mindedness in people through things like tech and social events…” (Weinstein)

For Weinstein, this dissolution of boundaries goes hand in hand with the way we learn. In the Western world especially, Weinstein has observed the role external motivation plays in our pursuit of knowledge. Learning is transactional, something that offers returns in the form of respect, money, hierarchical positions, and the like. What if we shifted our values to learn open-mindedly, for the sake of learning, embracing different perspectives? This mindset, in combination with legislative change, might offer a way into tackling thorny institutional issues.

“…what led me to that different perspectives aspect is the importance of compassion in a person’s life, of caring for the people around you, caring for people that are different than you, and trying to learn that through life, to me, is a process of experience, of experiencing different perspectives. And so it becomes a thing of, how can we encourage people to experience different perspectives, to see things in different ways?” (Weinstein)

Thus, Weinstien is preparing a “Living Futures” event:

“…a fusion of hackathon, Case Competition, Social Innovation, art studio, and having people actually intermingle between those different aspects, get those different perspectives, and see how that affects the projects, and the unique ways they can approach the different problems that will be presented at the event for people to work on.” (Weinstein)

Interdisciplinary innovation can take place along every step of the research process—from asking the right questions, as highlighted by Zhou, Raniuk, and Concepcion, to the very act of acquiring the information to answer these questions, as Weinstein demonstrates.

Like all research, interdisciplinary research requires resources. In order to create these sorts of connections and innovations, we have to advocate for increased funding—both direct funding and indirect funding through spaces like Building 21.

Nick Cholmsky [Appendix 1I] McGill, has shared with us the importance of financial support for unconventional projects. Cholmsky travels around Canada giving talks to boys across various high schools and middle schools with the goal of helping them connect with themselves outside of the social pressures of conventional masculinity. Various aspects of these boys’ lives are presently coloured by expectations for masculinity, including mental health, body image, friendships, and relationships. Cholmksy hopes to encourage each individual to find their own version of masculinity. But this takes more than just dedication and drive:

“The reality is I’m still a college student. I need to be able to sustain myself. The work that I can do is fairly limited because I need some schools to pay me.”…

“But I do want to be able to reach as many people as possible; with a little bit of extra funding, I want to be able to take this to social media and create helpful videos. I want to create an assessment of impact; I want to figure out how we are influencing these kids so that we can create a presentation that is as effective for these young people as possible.” (Cholmsky)

There is no doubt that Cholmsky’s work, along with the myriad of other Building 21 scholars’ work, is imperative in our increasingly siloed world. But without the necessary resources, such work reaches its limit. Individual bright minds and collaborative spaces alike need help to thrive.

Nick Cholmsky: Liberating Masculinity

Building 21 Has Been an Important Space for Many

B21 has played a crucial role in various BLUE Scholars’ journeys.

Victoria Macheroub Kramer, whose podcast is uncovering the connections between neurodiversity, entrepreneurship, and innovation, says:

“B21 really gave me a space to explore however I wanted to explore. It also has put me within a community of people who are from completely different backgrounds. You know, there’s some undergrads, post docs, people who are doing poetry, people who are doing physics, engineering, really anything. And so they really all do come together. There are some discussions which help you look at things in a different way. I feel like it’s really about exploring something rather than looking for a result, which I feel is the main difference between B21 and traditional research.”

Emily Zheng, whose podcast is exploring and breaking down disciplinary boundaries, says:

“Building 21 is definitely a beautiful place to investigate this [the topic of disciplinary barriers], because I think Building 21 is probably the only space on McGill campus that brings together people from very diverse backgrounds and of all different levels. Like there’s undergrads, there’s masters, there’s PhDs, and they’re all studying different things. Every single person’s project is about something different, and they’re all very important topics. The beauty of it is, when you clash everything together, there’s so many new perspectives that these ideas are on another level. You can dig as deep as you want into finance, but you’re still stuck in the world of finance. Whereas if someone in science comes to give a twist on it, it becomes this beautiful blend of disciplines.”

Anastacia Raniuk and Isabella Zhou, who are working on the collaborative brainstorming project, “A Regenerative Economy: How Can We Achieve Growth while Healing Nature?” say:

“We figured that Building 21 would be the perfect space to explore this question, because it’s such an interdisciplinary area with so many different scholars and students with a variety of fields.” (Raniuk)

“I think a key part about Building 21 is it’s such a big, beautiful space with new ideas and collaboration. It’s a free space for discussion and discovery.” (Zhou)

These testaments to the open and collaborative nature of B21 speak for themselves. Supportive spaces for interdisciplinary and unconventional research are highly valuable to this generation and our collective future.

Advice for Beginning Interdisciplinary Research

We asked some of our interviewees their advice for those struggling to bridge the gap between their discipline(s) and others. Here are a few eloquent excerpts of their responses:

“I’d say to anyone who’s looking at doing an interdisciplinary project or going between disciplines like this, embrace the fact that you have a lot of different talented views on life. Everything that you do in one aspect of life, these are not silos. They’re not different strata. They bleed into each other and they inform each other. Keep your mind open and understand that everything that you see in one place can be applied in another.” (Guo)

“I would say that they should get involved in spaces like Building 21 or try learning from, whether it’s books or media, or just meeting people that are in fields that they normally wouldn’t be interested in and you’ll be surprised to find how much you might have in common.” (Raniuk)

“I would encourage them to have bravery, courage to take that step up. But it does take a village. Without Building 21 here, I wouldn’t be as confident sharing my work with the people around McGill. This was a great platform that really helped me out. And so I encourage them to either find another group that has the same kind of views, or start their own if one doesn’t exist.” (Cholmsky)

B21 Presenter Sarthak Mendiratta [Appendix 1J], a Physics and Computer Science Student at McGill, offers profoundly thoughtful advice for anyone who wants to begin interdisciplinary research. This is an inspirational perspective for anyone looking to wade into the shallows of a new field, the depths of which they cannot yet even begin to fathom. Mendiratta’s presentation entitled “Where Does God Exist? Mapping the Cosmologies of Religions” aims to analyze then map different religions and their respective cosmologies. Mendiratta describes a religion’s cosmology as its different “planes of reality” or realms (which often interact with each other). Mendiratta is now using graph theory, and by extension computer science and mathematics, to represent these cosmologies.

The project has Mendiratta stretching beyond the scope of Physics and Computer Science and interacting with Religious Studies Professors and Anthropologists. Mendiratta explains that collaboration with people from other fields helps ensure that the project is academically rigorous:

“That’s sort of a prerequisite, something I wanted personally—for this project to be academically rigorous.” “To have people that I can talk to from different fields and to learn how they can contribute to the project, how they can be a part of the project, is very, very important.”

“At the end of the day, I’m using knowledge that I gain from my academic training and just attempting to deeply understand the problem. If I was an arrogant physics student who didn’t care about what religious studies people or people from anthropology think about, I wouldn’t be able to tackle this problem.” (Mendiratta)

Mendiratta sets a precedent for science students and all students for that matter, but particularly those who do not acknowledge the importance of disciplines that are not their own. Mendiratta addresses such narrow-mindedness head on:

“You’ll see people who look down upon certain fields. But when you go deeper into a subject, you realize that everything is very tied together. There’s a lot of beauty to be explored in these deeper concepts.”

Mendiratta encourages scholars to venture beyond the safety of the knowledge they’ve acquired and respectfully traverse into fields beyond:

“ ‘I stand on the shoulder of giants’ is a very famous line within the scientific community.”…

“You have to respect the work that is already done in a field. You have to try to understand it deeply, and then use your skill set to hopefully apply it.”

Sarthak Mendiratta: Where Does God Exist? Mapping the Cosmologies of Religions

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” (Newton)

Thank you for reading. We hope these B21 students have inspired you as they’ve inspired us. We encourage all undergraduate students to consider the possibilities of interdisciplinary and unconventional research. That being said, we hope to see your innovative and collaborative works featured at next year’s Undergraduate Science Showcase!

Works Cited

Building 21 – McGill University’s Interdisciplinary Idea Lab, McGill University, www.building21.ca/.

Cholmsky, Nick. Interview conducted by Kiarah Geertsema, 25 Mar. 2025.

Concepcion, Roberto. Interview conducted by Natalie Co, 25 Mar. 2025.

Guo, Isabelle. Interview conducted by Kiarah Geertsema, 25 Mar. 2025.

Liang, Laurence. Interview conducted by Kiarah Geertsema, 25 Mar. 2025.

Macheroub Kramer, Victoria. Interview conducted by Natalie Co, 25 Mar. 2025.

Mendiratta, Sarthak. Interview conducted by Kiarah Geertsema, 25 Mar. 2025.

Newton, Isaac. “Isaac Newton Letter to Robert Hooke, February 5, 1675.” Historical Society of

Pennsylvania Digital Library, digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/objects/9792.

Raniuk, Anastacia and Isabella Zhou. Interview conducted by Kiarah Geertsema, 25 Mar. 2025.

Reed, Katherine. Interview conducted by Kiarah Geertsema, 25 Mar. 2025.

“Undergraduate Science Showcase.” Office of Science Education, McGill University,

www.mcgill.ca/ose/initiatives/undergraduate-science-showcase.

Weinstein, Joshua. Interview conducted by Natalie Co, 25 Mar. 2025.

Zheng, Emily. Interview conducted by Natalie Co, 25 Mar. 2025.

Appendix 1: List of B21 Projects and Associated Authors Interviewed* by The Abstract

- Uncovering the Connections Between Neurodiversity, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation.

Victoria Macheroub Kramer

- A Regenerative Economy: How Can We Achieve Growth while Healing Nature?

Aimee Li, Anastacia Raniuk, Isabella Zhou, Itai Epstein, Jovan Rohac, Nika Aghili, Roberto Concepcion, Sophie Potvin

- The Bridge.

Anu Khanna and Emily Zheng

- Building and Examining Biofutures with Speculative Fiction.

Isabelle Guo

- Improving Efficient Computing through Hardware and Software Co-Design.

Laurence Liang

- Lexicon to Deepen the Relationship between Humans and the Environment.

Erica Lin

- Preserving Privacy.

Katherine Reed

- Creation Beyond One Vision: The Many Lenses Shaping a More Human Technology.

Joshua Weinstein

- Liberating Masculinity.

Nick Cholmsky

- Where Does God Exist? Mapping the Cosmologies of Religions.

Sarthak Mendiratta

*All interviews occurred on March 25th, 2025, at the University Centre (Students’ Society of McGill University Building), during McGill’s 2025 Science Undergraduate Showcase.